These, then, are the truths at the heart of atonement. First, that something has gone terribly wrong. We find ourselves in a distant country far from home. Second, whatever the measure of our guilt, we are responsible. Then third, that something must be done about it. Things must be set right. We cannot go on this way. False gospels of positive thinking or stoic exhortations to make the best of it are worse than useless. They are obscene. They are invitations to make our peace with a corruption at the core of everything. Better that Job and all the Jobs on the long mourning bench of history should curse God and die than that they should make their peace with the evil that they know. Such a peace is the peace of the dead, of those who are already spiritually and morally dead. The religious marketplace is crowded with the peddlers of peace of mind and peace of soul. But the narcotic of denial or pretense is too high a price to pay. Better to rage against the night.

Something must be done about what has gone wrong. Things must be set right. And this brings us to the fourth great truth of atonement: whatever it is that needs to be done, we cannot do it. Each of us individually, the entirety of the human race collectively—what can we do to make up for one innocent child tortured and killed? Never mind making up for Auschwitz, or the killing fields of Cambodia, or the coffin ships of traffickers in human slavery, or the slaughter beyond numbering of innocents in the womb. We chatter on about modernity and progress while King Herod reigns secure. “A voice was heard in Ramah, wailing and loud lamentation, Rachel weeping for her children; she refused to be comforted, for they were no more.”

Rightly does Rachel refuse to be comforted. Something must be done. It started long before Rachel and her children. From far back in the mists of our beginnings, the blood of Abel has been crying from the ground; and along the way we have allowed ourselves to be comforted by the counsel of Cain, advising us to get over it, to get on with our lives, for, after all, are we our brother’s keeper? But we know we are. We don’t know what to do about it, but we know that if we lose our hold on that impossible truth, we have lost everything. Something must be done. Justice must be done. Things must be set right.

But what can we do? We cannot even put our own lives in order, never mind setting right a radically disordered world. The Apostle Paul declares, “I can will what is right, but I cannot do it. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do . . . . Wretched man that I am! Who will deliver me from this body of death?” There is an answer to that question, but do not rush to the answer. Stay with the question for a time if you would understand why the derelict hangs there on the cross.

If things are to be set right, if justice is to be done, somebody else will have to do it. It cannot be done by just anybody, as though one more death could somehow “make up for” innocent deaths beyond numbering. That way lies the seeking out of scapegoats, the vain effort to heap our collective guilt on another, on the “other.” People have been doing that from the foundation of the world. History is filled with scapegoats sacrificed to appease outraged justice.

And the Lord commanded Moses that Aaron should bring the goat before the Lord, “and Aaron shall lay both his hands upon the head of the live goat, and confess over him all the iniquities of the people of Israel, and all their transgressions, and all their sins; and he shall put them upon the head of the goat, and send him away into the wilderness. The goat shall bear all their iniquities upon him to a solitary land.” The goat goes off to a distant country. God Himself trained ancient Israel in the ritual by which justice was satisfied, but only for a time. It is a training for what was to come, and for what was to surpass it.

Through the myths of millennia, blind and stumbling humanity acts upon the unquenchable intuition that something must be done. From Canaanite altars to Aztec temples, countless thousands have been offered in blood sacrifice. In the cruel twists of mythic imagination, the scapegoat is not expelled but destroyed. In our own enlightened century a nation sought to purify itself and the world by the extermination of the Jews. Even today we witness mobs outside prison walls cheering the execution taking place inside. It is a long, terrible history of bloodlust and vengeance, all in the name of justice, all driven by the insistence—the correct insistence—that something must be done.

As much as we are repulsed by it, that long, terrible history bears witness to an intuition that cannot be, and should not be, repressed. Something must be done. Otherwise, we live in a world without moral meaning. Otherwise, forgiveness is Bonhoeffer’s “cheap grace” that trivializes evil and thereby also trivializes good. Otherwise, the elder brother, the one who resented his brother’s welcome home, was right in protesting that the reconciliation with the father is cheap and easy and dishonest. Forgiveness costs—it must cost—or else the trespass does not matter. Is such an intuition primitive? Yes, primitive as in primordial, as in that which constitutes our moral being in the world.

If we cannot set things right, if we cannot even set ourselves, never mind the world, right—who, then, is to do it? It must be someone who is in no way responsible for what has gone wrong. It must be done by an act that is perfectly gratuitous, that is not driven by necessity, by an act that is perfectly free. The act must be by one who embodies everything, whose life is not one life among many but is life itself—a life that is our life and the life of all who have ever lived and ever will live. But where is such a one to be found?

The opening words of the Gospel of John: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God; all things were made through him, and without him was not anything made that was made. In him was life, and the life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.” The one who is life itself does this because nobody else could do it. He who is light and life plunges headlong into darkness and death, and does so in perfect freedom. It is his mission, the reason he came into the world. “No one takes my life from me, but I lay it down of my own accord,” he said. “I have power to lay it down, and I have power to take it again; this charge I have received from my Father.”

The Father and the Son have colluded in a thing most astonishing, a thing on the far side of our ability to be astonished. Justice cries out to be satisfied; something must be done. From the blood of Abel, to the prison camps of Siberia, to the nine-year-old who this afternoon died of leukemia, justice cries out. These things must not be permitted to have the last word.

Who is at fault? Who is guilty? From the beginning of time, the wise and the good have wrestled with these questions. The wicked all have excuses. The guards at the death camps, the husband cheating on his wife, the executive padding his accounts, the physician giving a lethal dose of morphine in the nursing home—all have excuses. I was obeying superior orders; I have uncontrollable needs that must be satisfied; everybody does it; we must relieve the world of useless lives. Name the crime and it is fitted out with an excuse. My parents abused me; I was deprived; I was spoiled; my genes made me do it. And we are back to “Adam, where are you?” and his pathetic response, “The woman that you gave me . . . ”

All the Adams and all the Eves join with the brightest and the best of philosophers to declare that this is just the way the world is. And who is responsible for that? And with that question was born what philosophers call the question of “theodicy”—how to justify to man the ways of God. And thus was God put on trial. If God is good and God is almighty, how did evil come about? If there is evil, how can an almighty God be good or a good God be almighty? In order to adjudicate these questions, we constituted ourselves the jury and the judge, and we put God in the dock. And soon enough we would constitute ourselves the executioner as well.

From every corner of the earth, from every scene of every crime, from North and South, from East and West, from the rich and from the poor, every mother’s son and every father’s daughter gathered. The jury deliberated, and the jury reached its verdict. The decision was unanimous. With one voice, poor deluded humanity pointed to the prisoner in the dock and declared, “God is guilty!”

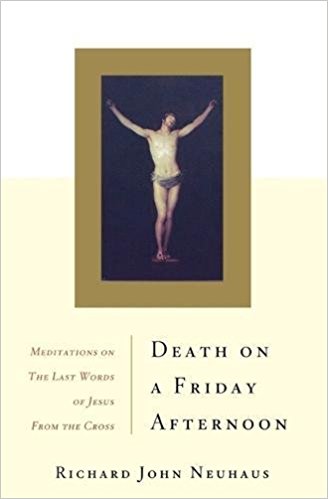

— from Death on a Friday Afternoon, by Richard John Neuhaus

Comments (5)

Thank you for posting this, Paul. I have read this book a couple of times during Lent and need to read it again soon. It is magnificent in both truth and style.

Posted by Beth | March 30, 2018 10:24 AM

So true. Whether you put it in typical Catholic terms (of sanctifying grace), or in standard Protestant terms (of justification), WE had not what it takes to do it. We were in the impossible position of being God's enemies, and in that condition anything we tried to do in repair would be defective, so we could not get ourselves out of that condition. Only Someone not in that position could do what we needed done.

I am sure that Neuhaus meant this "better ... curse God" as hyperbole. Even if we are headed to hell, it is ACTUALLY better to be less evil than to be more evil in hell. But Neuhaus's basic point is still true: we should not give up and treat evil as good and "just accept" our condition as the true normal. It isn't normal, it is contrary to who we are and in Whose image we were made. We should hold fast to the truth even if we ourselves cannot fix our condition. Better to admit the truth - that we are broken - and spend our days declaring defiance at brokenness than to call broken "sound" and to call crooked "straight". Better to don the armor and mount the horse and die charging at evil knowing full well we cannot succeed against it on our own, than to invite it in the home and sit it at the table and feed it the children it demands, as if doing so were somehow "better". Trying to become right and failing is still better than embracing being wrong, and thus becoming still more wrong.

Posted by Tony | March 30, 2018 1:19 PM

Another quote from Death on a Friday Afternoon that I posted today:

Richard John Neuhaus's _Death on a Friday Afternoon_, a meditation on Jesus's last words on the Cross, is a call to "linger awhile on Good Friday" rather than rush ahead to the Resurrection. He writes to those who have come to the Cross in faith:

"[N]ow, like the prodigal son, we have come to our senses. Our lives are measured not by the lives of others, not by our own ideals, not by what we think might reasonably be expected of us, although by each of those measures we acknowledge failings enough. Our lives are measured by who we are created and called to be, and the measuring is done by the One who creates and calls. Finally, the judgment that matters is not ours. The judgment that matters is the judgment of God, who alone judges justly. In the cross we see the rendering of the verdict on the gravity of our sin.

"We have come to our senses. None of our sins are small or of little account. To belittle our sins is to belittle ourselves, to belittle who it is that God creates and calls us to be. To belittle our sins is to belittle their forgiveness, to belittle the love of the Father who welcomes us home."

Posted by Beth Impson | March 30, 2018 8:39 PM

Thanks, Paul, fascinating quote from Neuhaus.

I was just thinking of the words to "Ah, Holy Jesus" where it says, "The slave hath sinned and the Son hath suffered." It suddenly dawned on me that that is a deliberate twist on the old, horrible custom of the "whipping boy," the boy who was kept as a companion for a young prince or nobleman and whipped in his place. The most classic scapegoat. Surely few more perverse customs have become embedded and normalized among so-called civilized men.

The whipping boy, of course, had no choice.

But this Son voluntarily suffered in place of the slave. The slave hath sinned, and the Son hath suffered.

Posted by Lydia | March 30, 2018 8:46 PM

Paul,

Thank you. I'm going to have to get this book since the passage you posted explains what I slowly came to feel but would never be able to express.

Posted by Tony S | April 1, 2018 10:43 AM